Third Evening

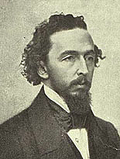

by Bayard Taylor

For days before, the wild-dove cooed for rain.

The sky had been too bright, the world too fair.

We knew such loveliness could not remain:

We heard its ruin by the flattering air

Foretold, that o'er the fields so sweetly blew,

Yet came, at night, a banshee, moaning through

The chimney's throat, and at the window wailed:

We heard the tree-toad trill his piercing note:

The sound seemed near us, when, on farms remote,

The supper-horn the scattered workmen hailed:

Above the roof the eastward-pointing vane

Stood fixed: and still the wild-dove cooed for rain.

So, when the morning came, and found no fire

Upon her hearth, and wrapped her shivering form

In cloud, and rising winds in many a gyre

Of dust foreran the footsteps of the storm,

And woods grew dark, and flowery meadows chill,

And gray annihilation smote the hill,

I said to Ernest: 'T was my plan, you see:

Two days to Nature, and the third to me.

For you must stay, perforce: the day is doomed.

No visitors shall yonder valley find,

Except the spirits of the rain and wind:

Here you must bide, my friends, with me entombed

In this dim crypt, where shelved around us lie

The mummied authors.Place me, when I die,

Laughed Ernest, in as fair a catacomb,

I shall not call posterity unjust,

That leaves my bones in Shakespeare's, Goethe's home,

Like king and beggar mixed in Memphian dust.

But you are right: this day we well may give

To you, dear Philip, and to those who stand

Protecting Nature with a jealous hand,

At once her subjects and her haughty lords;

Since, in the breath of their immortal words

Alone, she first begins to speak and live.

I know not, if that day of dreary rain

Was not the happiest of the happy three.

For Nature gives, but takes away again:

Sound, odor, color -- blossom, cloud, and tree

Divide and scatter in a thousand rays

Our individual being: but, in days

Of gloom, the wandering senses crowding come

To the close circle of the heart. So we,

Cosily nestled in the library,

Enjoyed each other and the warmth of home.

Each window was a picture of the rain:

Blown by the wind, tormented, wet, and gray,

Losing itself in cloud, the landscape lay;

Or wavered, blurred, behind the streaming pane;

Or, with a sudden struggle, shook away

Its load, and like a foundering ship arose

Distinct and dark above the driving spray,

Until a fiercer onset came, to close

The hopeless day. The roses writhed about

Their stakes, the tall laburnums to and fro

Rocked in the gusts, the flowers were beaten low,

And from his pigmy house the wren looked out

With dripping bill: each living creature fled,

To seek some sheltering cover for its head:

Yet colder, drearier, wilder as it blew,

We drew the closer, and the happier grew.

She with her needle, he with pipe and book,

My guests contented sat: my cheerful dame,

Intent on household duties, went and came,

And I unto my childless bosom took

The little two-year Arthur, Ernest's child,

A darling boy, to both his parents true,

With father's brow, and mother's eyes of blue,

And the same dimpled beauty when he smiled.

Ah me! the father's heart within me woke:

The child that never was, I seemed to hold:

The withered tenderness that bloomed of old

In vain, revived when little Arthur spoke

Of Papa Philip!

and his balmy kiss

Renewed lost yearnings for a father's bliss.

And something glittered in the boy's bright hair:

I kissed him back, but turned away my head

To hide the pang I would not have thee share,

Dear wife! from whom the dearest promise fled.

God cannot chide so sacred a despair,

But still I dream that somewhere there must be

The spirit of a child that waits for me.

And evening fell, and Arthur, rosy-limbed

And snowy-gowned, in human beauty sweet,

Came puttering up with little naked feet

To kiss the good-night cup, that overbrimmed

With love two fathers and two mothers gave.

The steady rain against the windows drave,

And round the house the noises of the night

Mixed in a lulling music: dry old wood

Burned on the hearth in leaps of ruddy light,

And on the table purple beakers stood

Of harmless wine, from grapes that ripened on

The sunniest hill-sides of the smooth Garonne.

When Arthur slept, and doors were closed, and we

Sat folded in a sweeter privacy

Than even the secret-loving moon bestows,

Spoke Ernest: Edith, shall I read the rest?

She, while the spirit of a happy rose

Visited her cheeks, consenting smiled, and pressed

The hand he gave. With what I now shall read,

He added, Philip, you must be content.

No further runs my journal, nor, indeed,

Beyond this chapter is there further need;

Because the gift of Song was chiefly lent

To give consoling music for the joys

We lack, and not for those which we possess:

I now no longer need that gift, to bless

My heart, -- your heart, my Edith, and your boy's!

Therewith he read: the fingers of the rain

In light staccatos on the window played,

Mixed with the flame's contented hum, and made

Low harmonies to suit the varied strain.

Source:

The Poet's JournalCopyright 1863

Ticknor and Fields, Boston